LinkedIn is a professional network used by 774 million people worldwide. Launched in the US in 2003, it has since successfully expanded to new countries despite the initial skepticism in some of the markets. But China was different.

In 2014, LinkedIn decided to expand to China which is home to around 140 million professionals. Just in 2018, over 8 million individuals graduated from universities in the country. But LinkedIn knew that its usual playbook would not be replicable in this market.

Derek Shen, hired to be the head of LinkedIn China, would report directly to the company CEO Jeff Weiner who was based in California. The team in China did their own development to localise the product beyond just translation. This level of autonomy and localisation was an exception at LinkedIn.

Even before officially launching in China, LinkedIn already had 4 million users there. They were mostly English-speaking professionals who had studied or worked abroad previously. It was the best platform for them to plug into the world.

Adapting their marketing

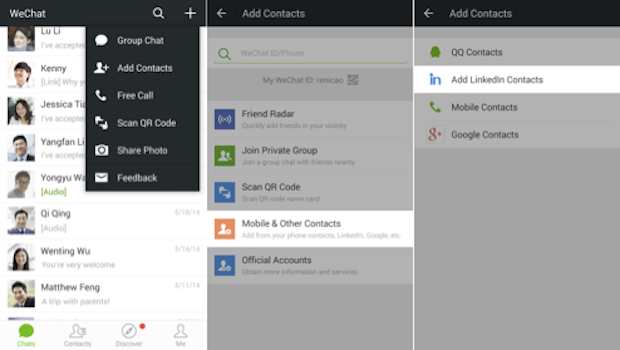

In most countries, LinkedIn’s growth had been driven by email and search engine optimisation. But that wouldn’t work in China where people prefer WeChat and phone calls. Also, a search for a person’s name on the local search engine Baidu was unlikely to return a LinkedIn profile.

LinkedIn operated significantly offline in China compared to the rest of the world. While it was not something headquarters was used to, they gave the local team full autonomy to decide on what marketing tactics would work best.

The team in China started running physical ads in the subway in cities like Beijing and Shanghai where 9 million people commute every day.

The team also organised hundreds of meet-ups where Chinese professionals could meet with global business personalities such as Reid Hoffman, Kai-Fu Lee and Peter Thiel.

LinkedIn engaged in celebrity endorsements. The professional network was endorsed by local celebrities such as the olympic gymnast Ning li and English teacher turned investor Xiaoping Xu.

On top of these promotional activities, LinkedIn added new features within its product to grow the user base. It added the ability to find people nearby as well as Chinese news recommendations.

With these initiatives, the number of LinkedIn users climbed from 4 million beginning 2014 to 9 million in the middle of 2019.

But none of these activities provided greater returns than the partnerships that LinkedIn embarked on.

Leveraging on partnerships

A key partnership for LinkedIn was the deal it struck with the super app WeChat in its early days. It consisted of linking WeChat to LinkedIn accounts. WeChat was not an ideal partner because its users had limited (or even fictional) information on their profiles. But the growth of the app, which eventually became China’s biggest social media app (with over a billion users), helped generate significant awareness for LinkedIn in China.

Another partnership that LinkedIn pursued was with Sesame Credit – a credit-scoring system developed by an affiliate of Alibaba. Users were incentivised for linking their LinkedIn profiles by being offered higher credit scores which provided perks such as easier access to loans. A win-win situation for all parties. This partnership proved to be fruitful for LinkedIn.

Slowed down by the headquarters

Despite the autonomy provided by the headquarters in the US, LinkedIn China started running into issues unique to the local market.

For example, the China team wanted to make some changes to the registration flow to cater for local users.

The registration was based on email. There was an assumption that everyone had an email but only a third of internet users in China actually did. Instead, they preferred signing up for services with their mobile number.

Making such a change required involving engineers based at the headquarters in the US. It was a slow process. A year after their launch in fast-moving China, LinkedIn still did not enable registration with a mobile number.

Something similar occurred when LinkedIn tried to integrate with the hugely popular online payment platform Alipay.

The LinkedIn China team also had limited budget for driving product adoption. In China, companies spend considerable amounts to acquire users as it is a ‘pay for play’ model. However, LinkedIn was used with the product selling itself and didn’t provide the budget required for them to truly compete in the Chinese market.

Failure to fully understand the market

LinkedIn also didn’t fully understand the needs of professionals in China.

LinkedIn’s ‘killer feature’ was its global network that users in China, especially those with overseas experience, could tap into. But people with overseas experience are only a very small percentage of all professionals in China.

Moreover, studying and working overseas is no longer the popular option for young Chinese professionals. There are now many opportunities in the country working for Chinese companies. The need for a global network has become less important.

Another hurdle for LinkedIn was the lack of Chinese user generated content (UGC) compared to English. As a result, Chinese users were not getting the same value out of the platform as in other markets. Creating professionally generated content (PGC) in the local language at scale was at odds with LinkedIn’s strategy and would have been too costly.

LinkedIn was also perceived as a boring tool by professionals. Relative to other Chinese social products, it was perceived as high-end and too serious which were not things that young professionals were expecting from a social app.

The meet-ups were also becoming less effective. People were attending because of the high-profile speakers but few ended up signing up for the platform.

Launching a separate app (Chitu)

In 2015, LinkedIn China made a bold decision. The team launched a separate professional networking app for the Chinese market exclusively named Chitu.

It was different from LinkedIn which was born in the PC era and was based around email. Chitu was mobile-first. It was targeted at non-English-speaking users while LinkedIn would remain the ‘high-end’ brand targeting users with overseas experience.

Chitu would operate like a startup. By not being integrated with LinkedIn’s standardised global product, it would be able to move fast.

Derek Shen made the case for Chitu by referencing the example of Tencent. Seeing the shift from PC to mobile, Tencent didn’t convert its popular web-based messaging service QQ but instead launched a separate app called WeChat which it built from scratch and which eventually became one of the most used apps in China.

The head of LinkedIn China had big ambitious for Chitu. He envisioned “a networking site so appealing to young Chinese professionals that it would eventually lead to a public stock offering for LinkedIn China”.

In just three months, in June 2015, Chitu was born.

Chitu addressed some of the problems that limited LinkedIn’s growth. It enabled registration with mobile numbers which was a long-standing problem.

It also added new features such as QR-code scanning for adding new connections and voice broadcasting to enable knowledge sharing from industry experts on career-related topics.

Challenges faced by Chitu

But beyond these few features, Chitu was not that different from LinkedIn. They were not like Tencent’s QQ and WeChat. Instead of complementing each other with each app having its separate set of users, they were competing with each other.

There were already a dozen of competitors in the space such as Tianji and Ushi. With its global network, LinkedIn offered something unique. But by cutting ties with LinkedIn, Chitu lost that differentiating factor.

Their biggest competitor however was WeChat. In the West, people have different social apps for their personal life (e.g. Facebook and Instagram) and for their professional life (e.g. LinkedIn). But in China, there is no separation between the two. People post about their job and about their family in the same app.

People were connecting on WeChat instead of exchanging business cards. There was no reason for them to use a separate platform for networking. Additionally, WeChat had features such as free audio and video calls which professionals started to rely on as part of their job.

Chitu’s advantage was its database of professional profiles. It had information on people’s job and skills. But this only appealed to headhunters, not the professionals for whom LinkedIn caters first.

Member First

One of the core values at LinkedIn is ‘Member First’ because ‘without our members, there’s no LinkedIn. Everything we do, we do for them.’

The appeal of Chitu was not evident for Chinese professionals. LinkedIn promoted growing one’s network and looking opportunities via ‘weak ties’. But it was a hard sell in a country like China where people prefer to meet and build ‘Guanxi’.

Guanxi

Guanxi is a Chinese term meaning relationships; in business, it is commonly referred to as networks or connections used to open doors for new business and facilitate deals. A person who has a lot of guanxi will be in a better position to generate business than someone who lacks it.

Source

Chitu pivoted by betting on knowledge sharing. Just in one year, it ran 1000 sessions of knowledge sharing. Its slogan changed from ‘the app that understands China’s professional networking the most’ to ‘the app that shares deep and interesting career knowledge’. But, that wasn’t enough.

LinkedIn’s competitors in China were also struggling. Tianji and Ushi exited the market in 2015 despite having millions of users. Others pivoted to become focused on job search.

In its effort to grow Chitu’s user base, the team ignored the LinkedIn app. All resources were diverted towards Chitu’s growth. Running the two products simultaneously proved to be hard as they were not complementary.

The LinkedIn brand started to lose its appeal. New users were still signing up but the engagement remained low. Headquarters had to intervene.

Shutting down Chitu and pivoting

In July 2019, four years after its launch, Chitu was shut down. Without leveraging on LinkedIn’s global appeal, it had no particular advantage relative to aggressive local rivals.

Today, LinkedIn still exists in China. However, it is not dominant in the market and is not expecting to make money anytime soon.

Its focus is now on providing career guides, salary insights, career Q&A sessions and e-learning facilities. The demand for this educational content on career development, especially from young professionals, has been more evident than that for online professional networking.

While the launch of a separate app was a failed experiment for LinkedIn, its expansion to China remains a relative success compared to other US tech companies such as Google and Facebook who have exited the market. LinkedIn was able to connect millions of Chinese professionals with each other and to the world.

Sources: Winning in China, Bloomberg, China Tech Blog, btrax